Transformation

In business and strategy, we talk a lot about transformation. Transformation can mean a lot of things, but culture has always taught us that it’s a big, deep, dramatic shift or change. A metamorphosis. Renewal. “A 180.” It feels big, expansive, complicated.

In an ironic sense, there’s a new definition of transformation that began in 2021.

Transformation means simplifying; simplifying the business to focus outward to new partnerships and branding. Here are some trending examples: GE splitting into three companies; J&J splitting into two separate businesses; Toshiba will soon be three firms. Even Pfizer, Merck, and GlaxoSmithCline have joined the more focused business club. This not so exclusive group includes IBM, Dell, Bath & Body Works, and Victoria’s Secret.

There is something lost in the intra-company transfers between divisions/business units of conglomerates. The market’s attention is given more to the overall performance of a conglomerate versus insisting on clear accountability for each unit. This makes sense because diversification does reduce volatility.

Meet ATAS

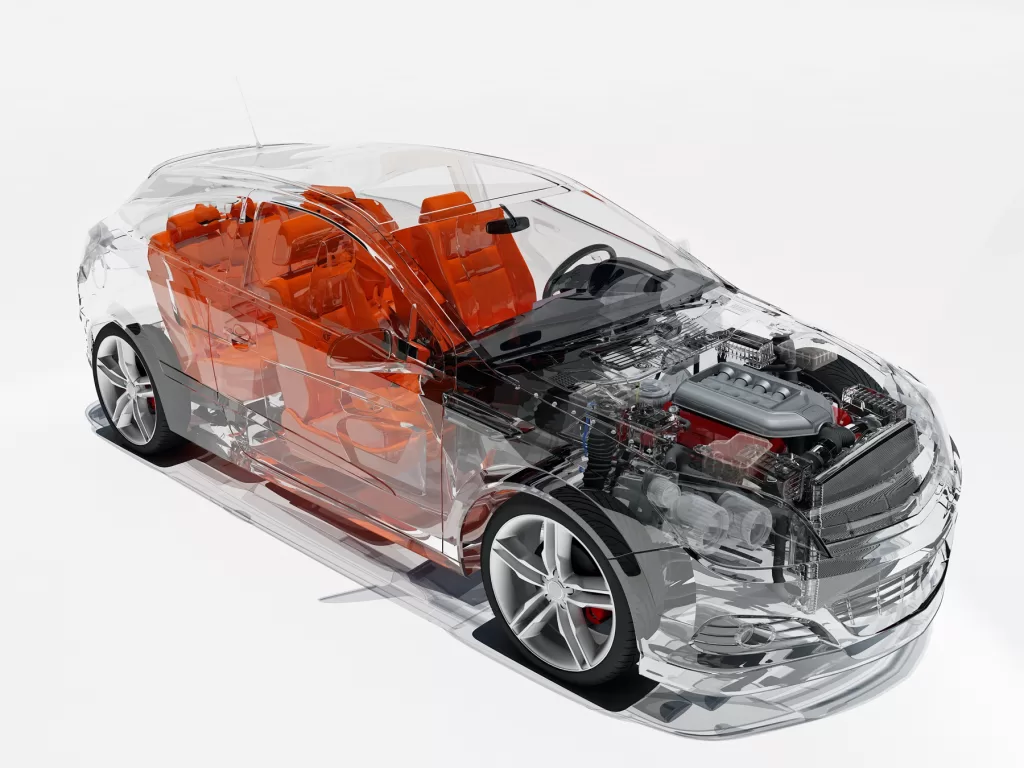

A client I will refer to as ATAS (A Tiered Automotive Supplier), for decades offered products that were basic in both materials and processes. As a result, the company’s culture shifted into autopilot. False significances were developed; concepts were introduced that weren’t tied to the work being performed. Gossip and perception became more of a reality.

When the challenge to move into the EV market was agreed upon, finding the true value creation of the company was difficult. To further complicate the effort, new products required new parts, new processes, and new technologies.

When Driscoll Organizational Solutions started to work with ATAS, they were frustrated, and rightfully so, because this latest attempt for outside support felt very similar to previous attempts by other consulting firms. As a result, they put up a wall. They withheld information. Assumed the latest consultants would pick up where the others had left off. They even sold the idea of my help differently to their constituents. Chaos ensued amid all the conflicting beliefs around the focus of the work together.

ATAS employees knew that a transformation was needed. Not within themselves and not in a way that addressed the actual flow of value.

There was also a larger issue – ATAS didn’t know who they were; they didn’t know what kind of company they were. What started as a manufacturer grew to include engineering ability. And they had become more reliant on the sales teams to break into the EV market.

Transformation Specific to ATAS

In the case of ATAS’s transformation – we simplified; I talked about agreeing that we needed to base their company’s transformation on their current capabilities. It was clear that they wanted to focus on new processes and technologies, yet they weren’t able to show they could follow best practices.

That’s hard to do in an organization like this – where there is very centralized decision making with low policy and process formalization. What this means is that people like to be creative in how they go about working or getting approval appears to be so subjective they find workarounds to get what the customer wants into production. Leadership sees randomness in how the work is done and demands that approvals be more strict with many leaders involved in the final decision. What could be a simple process – becomes more complicated, all while taking everyone – from the company to the customer – away from the original focus.

For ATAS

We implemented a storming phase. This is when and where different parts of an organization realize how different their views are when it comes time to take action.

We at first formed improvement teams for each functional area to align their efforts to the overall strategy. Time during the weekly meetings was used to challenge their assumptions about the other functions. This ensured they turned back inwardly to focus on what they knew as facts. We also ensured they didn’t assign tasks or make decisions for the other functions. After a couple of months, we started joint functional meetings. Sales and engineering, sales and finance, finance and engineering, engineering and operations, operations and supply-chain, etc. While the focus was the improvement, an underlying goal was to facilitate the hand-off of customer orders. We needed to formalize the flow from function to function and instill confidence across the functions.

Results

Like many of my clients, they needed to go slow to go faster. If details are being dropped as value is created, mistakes will get bigger the closer you get to the customer. One error in production ability cost one company millions a year for the whole duration of the contract.

ATAS is still working on alignment and flow. However, their customer orders are much more accurate with lead-times cut nearly in half.

I’ve cautioned ATAS against treating this latest need for change as a one and done. The focus was on the ability to change, not a specific ability. The world is already moving on to hydrogen. Or at least trying: Elon Musk’s hydrogen car

For other examples of transformation success see our Case Studies