Business Fundamentals

Success for any business comes down to the fundamentals of creating and delivering value. It has to do with leadership, the right mix of people, activities, and capital. Coordination of these elements are the most basic capabilities of any organization. Without doing them well, more complex activities like strategy are not possible. Suppliers, resources, competition, and culture can be obstacles, but they can also be advantages.

Business fundamentals still rule the day.

Business savvy people know there are no shortcuts. Leaders need situational awareness and the ability to put their circumstances into factual perspective. If they can effectively marshal internal and external capabilities in advance, then their odds of success increase exponentially. Unfortunately, all too often someone comes along claiming to have a surefire solution to make your headaches go away.

What is Getting in The Way

I have written quite a bit about why productized solutions like Lean fail. What I have not written a great deal about is how organizations can actually prevail. Winning comes down to either a company’s product or service, its brand, or having the lowest price. Focusing on anything other than these gets in the way of leaders aligning efforts to the what truly drives success. Below, I revisit the fabled story of Wiremold. Wiremold has long been held by the Lean community as proof that Lean works. Taking an objective view of the facts, I believe Byrne leveraging business fundamentals, along with the longevity of the brand, market share, and economic conditions led to Wiremold’s storied accomplishments.

Wiremold the Legacy

In the late 1980’s, the Murphy family found itself with an albatross of a company. Market share and brand recognition helped the company chug along, but poor profits were not going to leave much of a legacy. The Wiremold brand having been around for over seventy years at that point, had a bleak future. The four largest family stakeholders, who were about to enter their eighties, were looking for a way out.

They knew what the problem was but did not have the ability to solve it. They tried JIT (Just In Time) but the initiative showed lackluster results. In 1991, they crossed paths with Art Byrne.

When Byrne took over as CEO, Wiremold was valued at $30mm on about $100mm in sales. It was not difficult to see that working capital and operating expenses were the culprit of such an abysmal valuation. In addition, the company bureaucracy caused engineers to take 2 years to introduce new products.

Byrne’s formula for success while heavily influenced by working with Shingijutsu consultants, also included a great deal of business experience from Danaher. The consultants at the time had worked directly for Taiichi Ohno; the mastermind behind the Toyota Productions System (TPS). You can also see a good deal of similarity between Byrne’s style and Danaher’s earlier business model; the use acquisitions to increase book of business, product lines, and capabilities. While at Danaher, Byrne also learned the benefit of having a formal business system.

During Byrne’s time, inventory was significantly reduced, new products introductions were launched within 6 months, expenses were cut, and sales increased. All attributed by Byrne to quick changeovers, setting up value streams, and offering shorter lead-times on orders. I do not believe those are the factors that led to the large valuation and net profit margin when Wiremold was sold to Legrand.

What Really Happened

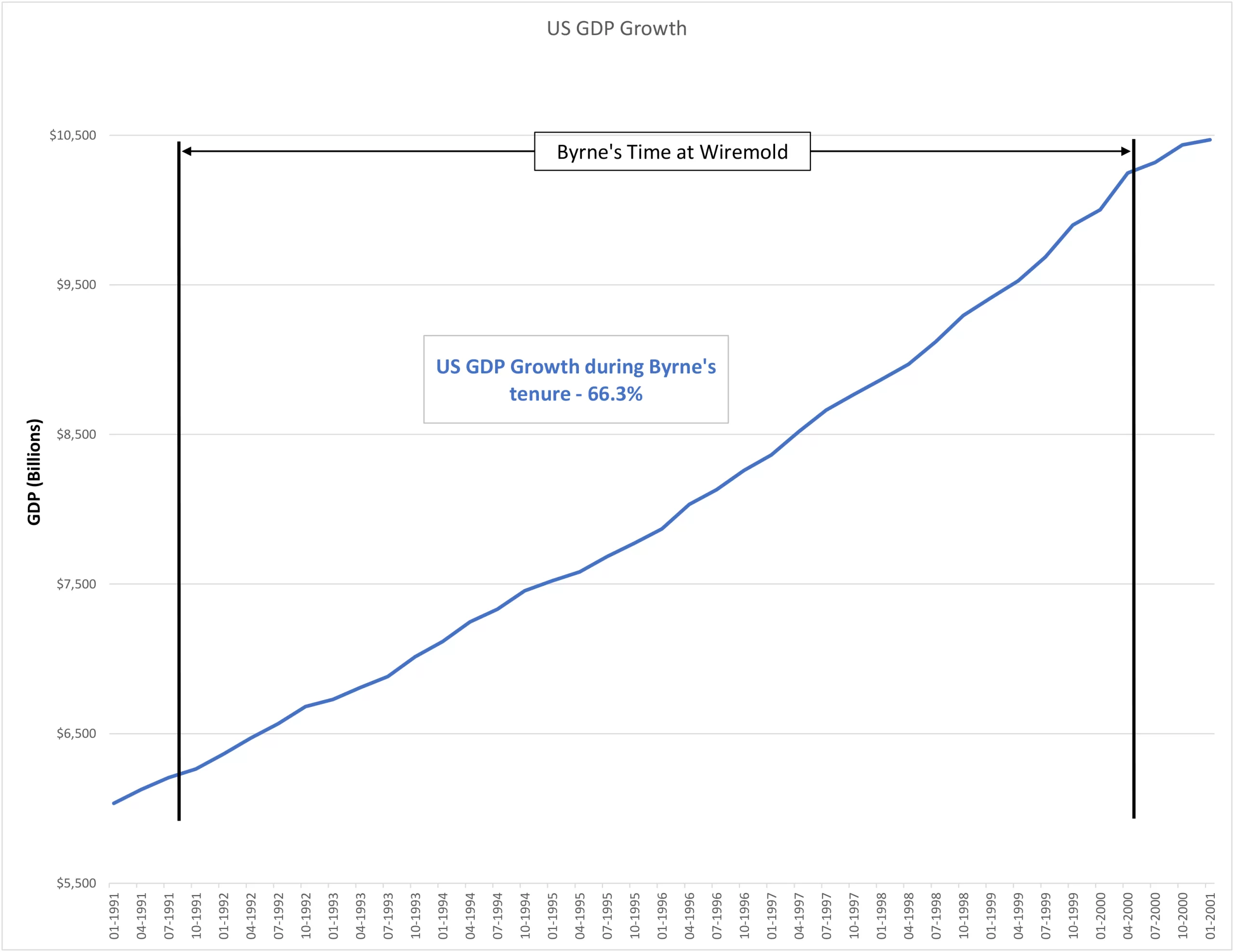

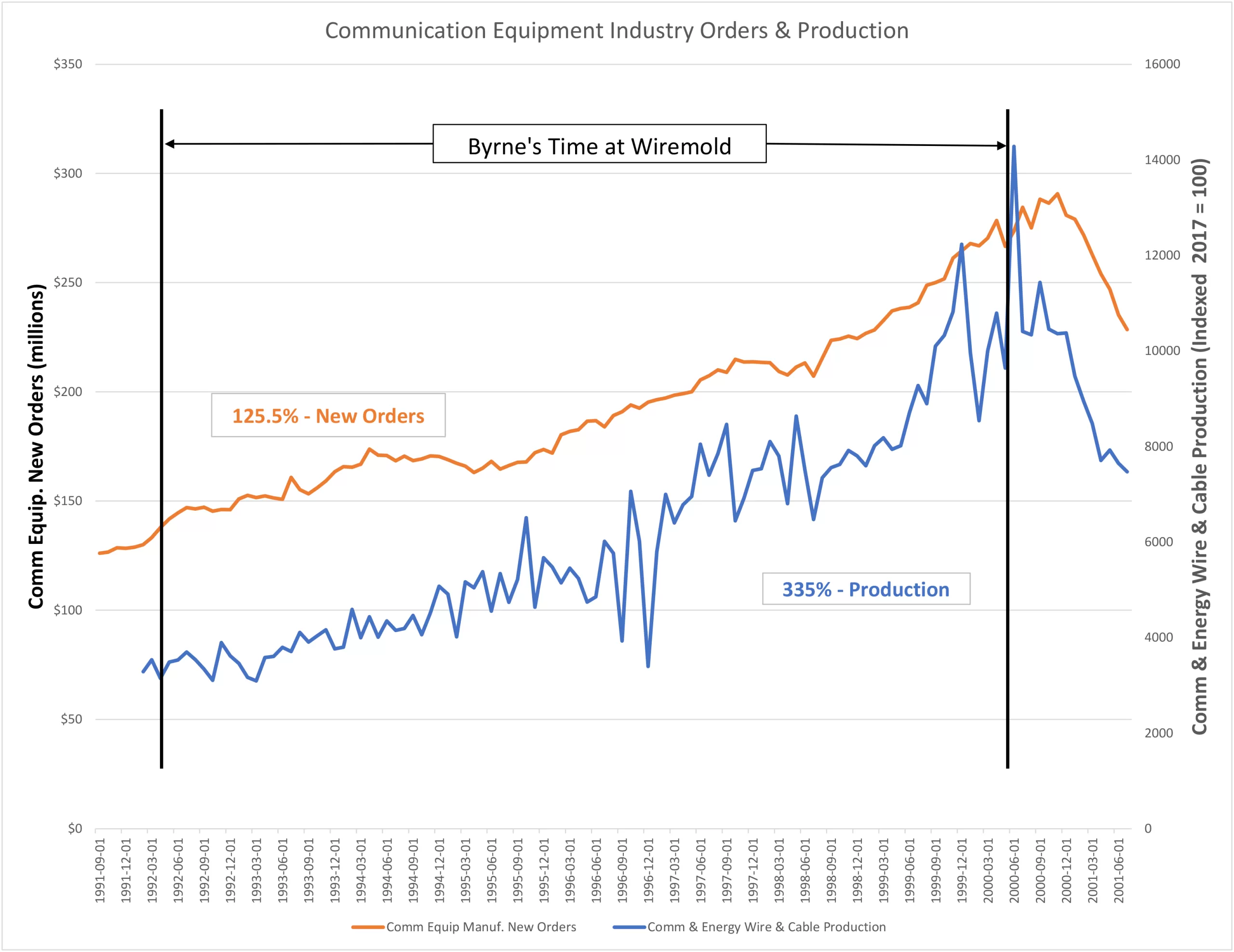

A few details that have been glossed over are what I believe to be the real drivers of Wiremold’s success. During Byrne’s tenure the US experienced the longest economic expansion in its history (See Figure 1). Not only that but Wiremold sold to the data & communication equipment manufacturing industry, which experienced a 335% growth in new orders. About the same percentage of revenue growth Wiremold itself enjoyed (See Figure 2).

There is no doubt that cash flow improved given the final company valuation of $775mm from the initial $30mm. What many discount or even overlook is the fact that over 50% of Wiremold employees were laid-off[1][2][3] within the first six months of Byrne taking the helm. Non-performing products were cut, and acquisitions were used to bolster capacity and refresh product lines. All of which are fundamental business practices; not lean or JIT. At the beginning of Byrne’s time, Wiremold employed approximately 1,000 employees across eight sites[4]. At the midway point, after several acquisitions, Wiremold had about 600 employees[1].

The people I have talked with who either reported to Byrne or worked at Wiremold during this time, speak of Byrne as a smart, business savvy individual. They all stated he had a unique charisma that enticed people to want to follow him. Leadership is a key ingredient to success in business and I believe Byrne had that.

Shifting The Blame

It is these tailwinds that were the biggest drivers to Wiremold’s success, not Lean. Byrne’s expertise is infused with the knowledge of Toyota’s tightly integrated production system. The acquisition by Legrand revealed the weaknesses of such a system when exposed to a broader market. Many have lamented about Legrand ignoring Wiremold’s inventory pull system and other characteristics of their tightly integrated manufacturing system, resulting in the collapse of Wiremold’s effectiveness. What I see is a non-flexible system that couldn’t adapt to a different, yet successful system. Note that the size of Wiremold at the time it was bought, only represented half of Legrand’s US presence.

Another indication of how economics drove success at Wiremold was the recession that happened months after the acquisition by Legrand. Legrand suffered a negative net profit the second year after buying Wiremold. When the economy was expanding Wiremold did well, when the economy experienced a decline Wiremold followed.

A Business Case That Misled the World

Most attempts at lean fail. Not so much the application of the tools like 5S or quick changeovers. But failure in the ability to create a strategic advantage against competition. Lean having no standard definition muddies any effects it is supposed to have on an organization. Those relying on Wiremold as a benchmark to achieve similar results must recreate the same initial conditions. In other words, it is impossible.

In his book on strategy (‘Good Strategy/Bad Strategy’), Rumelt tells a story in chapter 8 about a family-owned machine manufacturer. The owner took a three phased approach to turning the business around. The first phase was to improve quality, the second phase improved the technical expertise of the sales team, and the third phase focused on reducing costs. The owner’s resulting strategy was growing the business profitably. There was nothing about Lean in that story. Wiremold’s story could be written similarly and the actual transformation of the business to emulate the Toyota system, should never had been done. Then what about Byrne’s actual strategy in all of this?

Byrne talks about using a time-based competitive strategy[5][6]. There was no indication that time was of the essence given Wiremold’s greater than 50% market share. Time-based operations is not a strategy. Productivity is a category of strategy, but it involves cost structures and improved use of assets. One way to improve asset use may be shorter lead-times but that creates little to no barrier to competition. The advantage it may give relies on the fact that customers will go elsewhere if they have to wait.

You Cannot Hide Your Strategy

The beauty of strategy is that it is openly observable. Looking back at Wiremold from 1991 to 2000, I believe the only strategy was the Murphy family exit. The year 1995 was pivotal for Byrne because of the threat of family members wanting to cash in. Byrne and Orrie Fuime (Wiremold’s CFO at the time) have talked about how buying back Wiremold stock would threaten the turnaround efforts. I believe there were many more options available[7]. Further, if the economy stalled at any point during Byrne’s tenure, whatever they were doing would have come to an abrupt halt.

What I believe was at stake was the amount of money that could be made through the profit sharing for the management team[8]. This seems to be the case with those touting Lean as their strategy. Another seems to be playing out now. Keep an eye on Culp at GE, because his actual strategy seems eerily similar.

For another example of Lean unduly getting the credit and management cashing out, read about the success story of the Dr. Pepper enduring brand here: Lean did nothing to change the trajectory of the business.

[1] ‘WIREMOLD FOLLOWING NEW PATH’, Hartford Courant, August 12, 1995 at 4:00 a.m. | UPDATED: August 25, 2021 at 3:03 p.m.

[2] Presentation “LEAN…IN THE END, IT’S ALL ABOUT PEOPLE”, Orest J Fiume, June 27, 2008

[3] https://www.encyclopedia.com/books/politics-and-business-magazines/wiremold-company

[4] ‘The Wiremold Company: Ensuring Shareholder Commitment’, Lawrence P. Grasso, Central Connecticut State University el al., 2015, pg. 12

[5] “Performance Measurement in a Lean Organization: The Case of The Wiremold Company”, Lawrence P. Grasso, Central Connecticut State University, pg. 3.

[6] https://www.leanexecs.com/art-byrne-video, “Time Based Competitive Advantage”

[7] “The Wiremold Company: Ensuring shareholder commitment”, Lawrence P. Grasso, Central Connecticut State University, pg 7

[8] Personal interviews conducted by the author of those who worked for Art Byrne and others who worked during Art Byrne’s tenure.